I’ve been going through a Franz Liszt phase again since around Christmas, when I brought his Piano Sonata in B minor (Claudio Arrau) and his Années de pèlerinage (Lazar Berman) along with me to California. Above all, I’ve been fascinated by his Études d’exécution transcendante because of their combination of extreme virtuosity and rich musical appeal. The twelve pieces are are supposedly among the most difficult to play in the classical piano repertoire. For me etudes 3 (“Paysage”), 5 (“Feux Follets”), 10 (“Allegro Agitato molto”), 11 (“Harmonies du Soir”) and 12 (“Chasse-Neige”) stand out, though the set as a whole remains one of Liszt’s strongest works.

Here are my comments on several different interpretations after listing to a broad selection of them.

A logical starting point is the 1974 recording for Philips by Claudio Arrau, who studied under one of Liszt’s pupils, Martin Krause. The great thing about Arrau is that he never loses sight of the music’s inherent expressiveness and poetry. However, it’s not his strongest Liszt recording, mainly because he takes some of the tempos too slow; pieces like “Mazeppa” and “Wilde Jagd” should have more fire in them. I do urge you to track down his now out-of-print 1970 recording of the Piano Sonata in B minor; he makes a powerful case for this work as Liszt’s masterpiece and one of the most innovative works of the 19th century.

Jenö Jandó‘s budget-priced recording for Naxos is thankfully still in print, and it’s actually one of the strongest overall interpretations of the Etudes as a whole. He plays with a great deal of freedom, giving the pieces an improvisatory feel without in any way seeming willful. I especially like the delicacy with which he plays the slower etudes such as “Paysage” and “Harmonies du Soir.” I also love his singing tone in “Chasse-Neige,” which brings out the piece’s long melodic arcs. On the other hand, he could have played “Wilde Jagd” faster and with more fury. Frequently you can hear him humming along with the music, but I don’t find it overly obtrusive.

Jorge Bolet, another major Liszt interpreter, is less successful in his 1980s recording for Decca/London, which is out of print individually but is still available as part of a pricey box set. Despite his fine playing, his consistently slow tempos drain the etudes of the energy that they need in places. There should be more variation in tempo across the set as a whole.

I was initially bowled over by Evgeny Kissin‘s recording of five of the Etudes (along with Schumann’s Fantasy, Op. 17). Certainly his execution of “Chasse-Neige” is awe-inspiring as an example of Romanticism in the grand manner. But he plays “Feux Follets” in an overly fast and showy manner, missing out on its airy, mercurial quality. Yes, it’s amazing how fast he can play it, but that’s not the point of the piece–the tempo is marked as “Allegretto.”

The most completely satisfying interpreter to my ears is still Lazar Berman. His 1958 mono recording is the only one widely released on CD, which is a shame. Although that interpretation is excellent, it has always suffered from distorted sound due to weak audio engineering. Much more satisfying is his 1963 stereo recording for Melodiya, which was released on LP in the West by Columbia in the 1970s. Apparently there was a Japanese CD of that recording, but it’s almost impossible to track down now. I ended up purchasing the LP on Ebay. There’s no shortage of fearsome virtuosity in movements like “Mazeppa” and “Wilde Jagd,” but Berman also plays the slower movements with great subtlety and lyricism. In particular he brings out the forward-looking qualities of “Harmonies du Soir,” which anticipates Debussy in its harmonics and keyboard textures. (As do some of the pieces in Années de pèlerinage, especially in Book 3; I strongly recommend Berman’s recording of this set as well.) Berman’s “Feux Follets” stands out for the way he brings out the melodic figures in the left hand – no small feat considering the many rapid leaps required. The capstone of the set is “Chasse-Neige,” in which he foregrounds as a great musical composition through his meticulous phrasing and voicing. This is where the improved engineering of the 1963 stereo set really pays off. I also love the way Berman gradually builds the tempo up to the piece’s devastating climax. There are still many great classical recordings not readily available on CD, but this is a mystifying oversight. Hello Melodiya? Columbia?

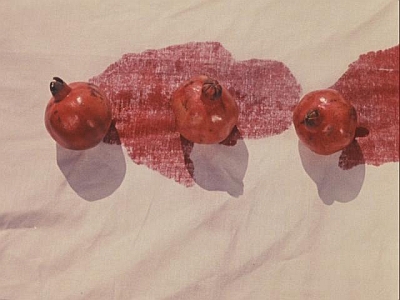

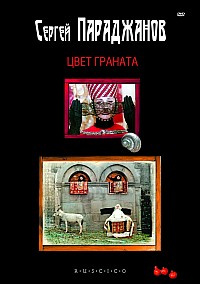

Last night I was finally able to see the new subtitled Russian Cinema Council DVD of Sergei Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates (1969) and can now do a comparison of all the existing DVD editions. Ruscico’s subtitled edition of the Yutkevich cut reinstates missing footage and thus corrects the disastrous audio sync problem which ruined their earlier unsubtitled edition, part of a “Best of Armenfilm” box set for the Russian market. However, we are still left with no wholly satisfactory version of the film on DVD anywhere. At the bottom of this post I will include some frame grabs for illustration. Click on each image to view a full-sized, properly scaled version.

Last night I was finally able to see the new subtitled Russian Cinema Council DVD of Sergei Parajanov’s The Color of Pomegranates (1969) and can now do a comparison of all the existing DVD editions. Ruscico’s subtitled edition of the Yutkevich cut reinstates missing footage and thus corrects the disastrous audio sync problem which ruined their earlier unsubtitled edition, part of a “Best of Armenfilm” box set for the Russian market. However, we are still left with no wholly satisfactory version of the film on DVD anywhere. At the bottom of this post I will include some frame grabs for illustration. Click on each image to view a full-sized, properly scaled version.